The world of work is ever changing and perhaps forever changed by the pandemic. From the factory days of America in the 1970s that Bruce Springsteen often describes in his music, to the pandemic-accelerated home-working days of today, the way we work has changed dramatically in just a few decades.

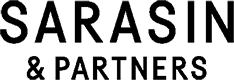

The shift has been undoubtedly accelerated by the pandemic. As we emerge from government restrictions, most advanced economies have either regained, or are close to regaining, their lost output. Labour markets, however, continue to bear scars. Having initially soared to almost 15%, the unemployment rate in the US has since fallen back to around 4%, yet the total employment pool is still 2.9 million people short of the pre-pandemic level (figure 1). These formerly employed people have gone either into the unemployment pool (0.6 million, or one fifth) or have left the labour force pool altogether (2.3 million, or four fifths), that is, not employed nor looking for work.

The process of labour market adjustment is often a slow one, and the rate at which data is published, based on household surveys, is even more so. How the labour market adjusts from this shock is uncertain, and will have important ramifications for wages, inflation and policy settings.

Why the labour shortfall?

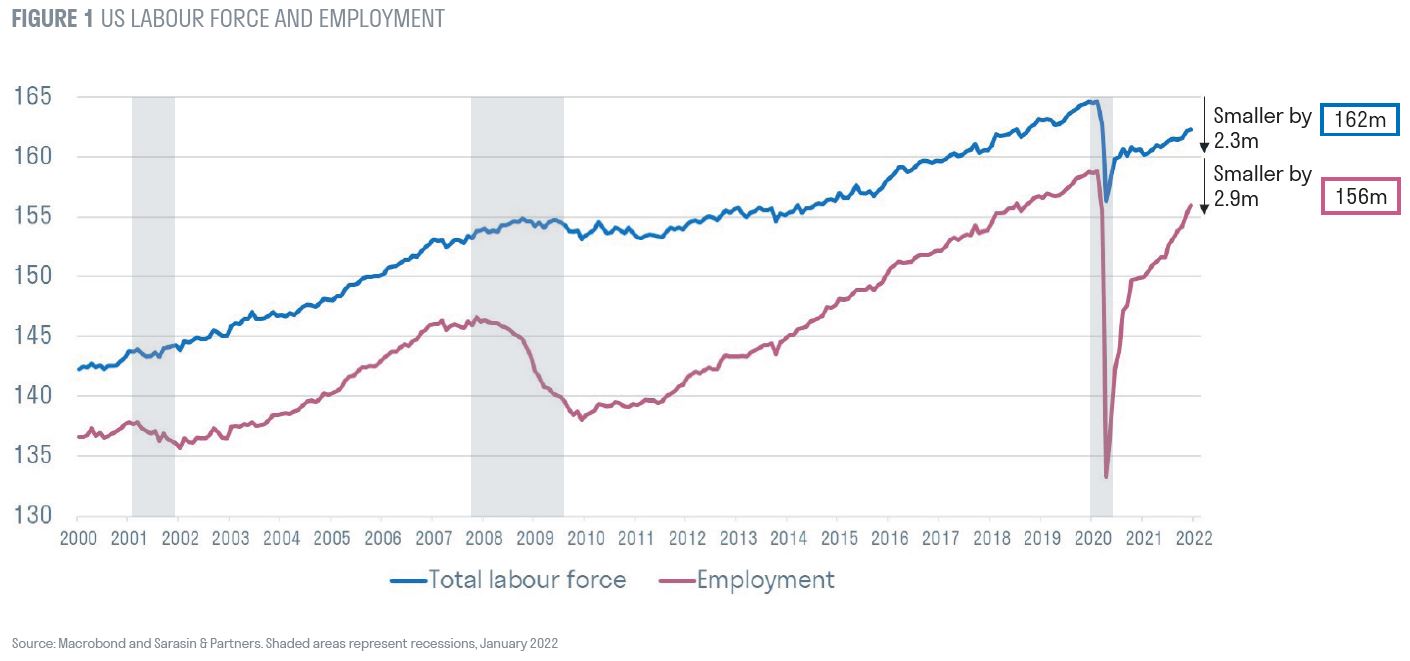

In any recession, labour market gyrations and flows from unemployment to employment are expected, but it is the current 2.3 million shortfall in the labour force from the pre-pandemic level, and its persistence, which is surprising in the aftermath of the current recession. What are the drivers behind this labour shortfall? We identify five factors that could be responsible.

Firstly, data shows that women appear to be disproportionately represented amongst those who are leaving the labour force. Figure 2 shows the breakdown of the current labour force shortfall by age and sex; women in their prime working age (defined as those aged between 25-54) represent one quarter of the total exits.

This may well be the unintended consequence of school closures, the reduction in available childcare and the disproportionate share of childcaring responsibilities that women often bear.

The other striking feature that is apparent in the chart is that those over the age of 55 years represent another quarter of those leaving the workforce. Many may well have taken the opportunity to accelerate their retirement plans. Faced with greater health risks, and perhaps having also benefited from rising asset prices, it is unlikely that this segment of the workforce will be lured back to their previous roles.

The remaining half of exits can be viewed in light of other, potentially overlapping factors, but also each a key driver in their own right.

Health concerns are cited as a key reason for some workers, especially those in high-social contact sectors, from re-entering the workforce. This is not surprising, but fortunately likely to be a temporary factor and bound to reverse as concerns over the disease dissipate over time.

The other, perhaps less appreciated, factor is migration. In many countries, migration accounts for more than one half of population growth, and migrant workers are often over-represented in the health, social care, and hospitality sectors of the economy. Those are the sectors most affected by the pandemic.

This factor has been particularly important in the UK, where the shock to the economy created by efforts to control the pandemic has been compounded by the UK leaving the EU and the end of the transition period in 2021. The EU was a key source of workers for a number of sectors. Indeed, acute worker shortages experienced in the agricultural, driver haulage and social care sectors have prompted the government to announce temporary 12-month visa streams.

Lastly, a portion of the current labour force drop-outs may reflect the so-called ‘Great Resignation’ trend. In the US, record number of workers are leaving their jobs every month. The health crisis may have instigated a broader holistic re-think by some to leave unfulfilling jobs and to re-assess their work-life options. A high quit rate is, generally, viewed as a sign of optimism over the economic outlook, but with the economic recovery remaining tepid, this high quit trend could prove more long-lasting. Anecdotal evidences also suggest that it appears more common in low-wage industries, where generous sign-on bonuses are proving insufficient to lure workers back.

Incentives not to work?

The pandemic was a no-fault recession, and governments – having learnt the lessons of the financial crisis of 2008/09 – “went early, went hard and went households”.

In the US, under three rounds of fiscal stimulus cheques, eligible adults could have received a total of $3,200 since the start of the pandemic, with a family of four receiving as much as $11,400. In the UK and many European countries, governments subsidised up to 80% of workers’ pay through furlough and short-term work schemes. Income protection schemes (US) and job protection schemes (Europe) supported household incomes, and given reduced opportunities to spend, propelled household savings rates to record highs.

In addition, households may also have taken the opportunity to diversify their sources of income from non-traditional sources of work.

A survey of European households suggests that as many as one in three currently receive ancillary income from online content creation platforms, e-commerce and non-fungible token /trading platforms. Of this grouping, as many as 25% plan to leave their current jobs within six months to pursue these activities full-time. This, combined with government efforts to support people’s income, may have changed the incentive structure to work in traditional roles.

As a result, the minimum threshold to entice people into work, known as the reservation wage, has increased. Data from the NY Fed shows that the average reservation wage has increased to just over $70,000 – up almost 10% over the past two years. This is turn has increased employees’ bargaining power and shifted the balance of power to a worker’s market. We expect that these drivers will mean that strong wage growth will be a key feature of the post-COVID economic landscape.

What will this mean for policy?

Central banks, tasked with the role of ensuring stable price growth, will be focused on these labour market dynamics. Thus far, labour shortages have led to the first-round effects of higher wage growth. Latest wage indicators suggest annual wage growth of around 4% in both the US and the UK.

Whether it leads to second round effects – higher wages triggering higher consumer prices – will be important to watch as it could lead to a spiralling wage-price feedback cycle which could prove hard to break. With inflation at 6.8% in the US and 5.1% in the UK, there is little room for policy error. With this in mind, the Bank of England increased policy rates in December 2021, and we expect the Federal Reserve to do the same in the US in March 2022.

Central banks, however, cannot engineer a mass return to the labour force, or hold back the tide of structural changes unfolding in the economy. Three quarters of those having left the US labour force may not return, or perhaps may return in a different capacity. New jobs created will not necessarily displace old ones, but will reflect the changing skills needs of the economy – potentially at both ends of the skills spectrum, in high-skill and knowledge-based roles as well as at the lower-skill and more precarious work spectrum. Importantly, it will be the role of politicians and governments to facilitate the transition to the new economy that emerges in the wake of the pandemic. Thankfully, it will also mean that The Boss (Bruce) may find himself abound with fresh material to recount the realities of the new working life.