UK interest rates are on an upwards trajectory, but the economy’s increasingly fragile state means further hikes could be modest.

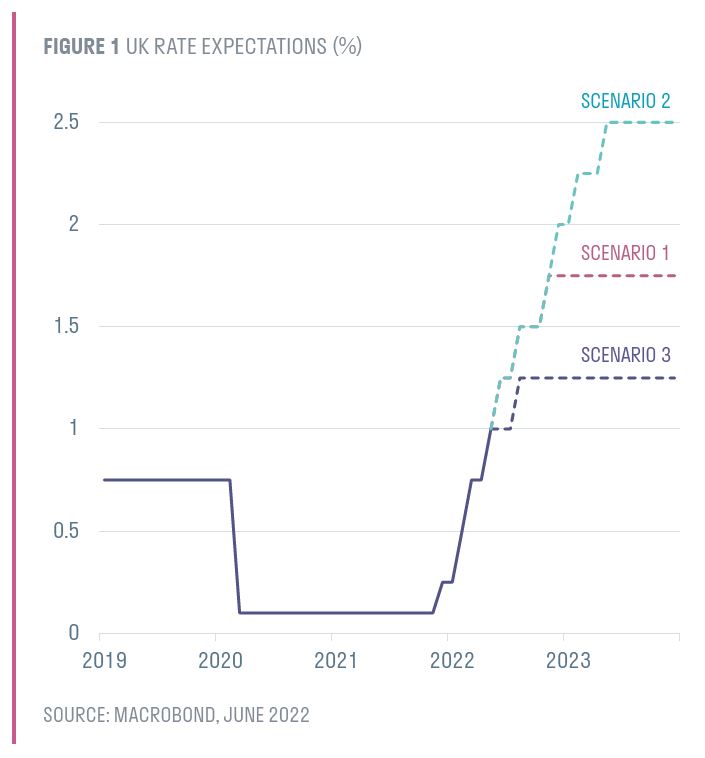

In the depths of lockdown, few people imagined that UK inflation would surge to a 40-year high of 9.1%, or that interest rates could rise so swiftly from their pandemic emergency levels of 0.1% to 1.25% today. As inflation globally began to accelerate in a world awash with liquidity, central banks were adamant that this would be a ‘transitory’ phase caused by the pandemic’s dislocation of supply and demand. Inflation would fall back naturally as the world got ‘back to normal’. Whether high inflation could have been avoided, given the vast levels of stimulus by governments and central banks, is difficult to gauge. What is clear is that any hope of a return to normal was dashed, first by a resurgence of COVID-19 that prompted China to re-implement draconian lockdowns, and secondly by the twin shocks to energy and food markets delivered by Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine.

Whether high inflation could have been avoided, given the vast levels of stimulus by governments and central banks, is difficult to gauge. What is clear is that any hope of a return to normal was dashed, first by a resurgence of COVID-19 that prompted China to re-implement draconian lockdowns, and secondly by the twin shocks to energy and food markets delivered by Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine.

A large proportion of current inflation is due to high global energy prices, resulting in electricity and gas prices in the CPI basket rising by 54% and 95% respectively over the year to May. The surge in inflation, however, is also becoming more broad-based and 85% of the CPI basket is now recording inflation above 3%. Core inflation, which excludes alcohol, food and energy is at around 6%.

Ensuring price stability is an important anchor for economic stability, which is why central banks’ policy focus has changed so dramatically in a short pace of time; their most pressing problem is no longer unemployment but inflation.

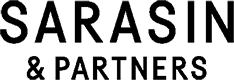

Financial markets currently imply UK policy rates to reach 3.25% by the middle of next year. We believe that such levels of rates are unlikely given a combination of factors, including long-term economic fundamentals, the current state of the UK economy, and underlying drivers of current inflation. In our baseline scenario, we expect policy rates to reach 1.75%.

Finding neutral

The Bank of England (BoE) has tightened policy at a relatively gradual pace so far, raising rates in 25bp increments since December 2021. This contrasts with the US Federal Reserve, which recently raised policy rates by 75bp in just one month. Comparisons between the two economies firstly lie in the fact that BoE began its rate tightening cycle several months earlier than the Fed. However, it also reflects fundamental differences between the two economies and their current state of health.

The BoE will be aiming to achieve a ‘neutral’ interest rate – the Goldilocks level for inflation-taming, at which monetary policy is neither expansionary nor contractionary and thereby keeping inflation constant. The appropriate neutral rate varies from country to country and depends upon an array of factors that includes demographics and productivity growth. Our analysis indicates that the neutral rate for the UK lies between 1.5% and 1.75% (see figure 1), whereas for the US it is likely to be significantly higher, at around 2.5%.

As such, our base case scenario is that the Bank of England raises policy rates a further two times to take interest rates to 1.75% (scenario 1).

In contrast, we expect the Fed to raise rates to 3.25%, higher than the neutral rate, to cool the overheating US economy and create sufficient slack in the labour market by raising the unemployment rate.

Our judgement is that much of the rise in UK inflation has been driven by external forces – especially energy input prices, supply shortages and import prices.

Inflation trajectory is key

The other key reason for our rates outlook relates to the health of the UK economy. GDP monthly outcomes suggest that the UK economy has stalled since January . We see a rising risk of recession, as high inflation, waning fiscal support and higher interest rates push the economy to the brink. Surveys suggest that consumer sentiment is currently at the lowest level since records began in 1974, and consumers are spending less on essentials.

It will be difficult for the BoE to raise rates and engineer a soft landing, and the path for rates largely will depend on the inflation trajectory. In the short term, we expect that inflation will continue to rise, reaching a peak of over 10% in October when the energy price cap for 15m households increases. Thereafter, base effects will force inflation to trend sharply downwards, reaching 2.5% by the end of 2023.

Yet, the risk lies clearly on the upside. For central banks, the worry is that the longer inflation remains above target, the greater the risk that inflation becomes embedded in price-setting behaviour, causing a change in inflation expectations, and in turn, wage demands. Once wage growth accelerates in response to high inflation, it can set off a vicious price-wage spiral, reminiscent of the late 1970s inflationary episode.

Supply constraints and sterling

The question of how much higher policy rates can rise also depends on an assessment of the drivers of inflation and whether monetary policy can address the underlying source.

Our judgement is that much of the rise in UK inflation has been driven by external forces – especially energy input prices, supply shortages and import prices. The costs associated with the UK leaving the EU has also played a role, but this effect appears to be diminishing, according to the BoE’s Michael Saunders.

On the other hand, if domestic sources of inflation prove to be larger, then the calculus could be different and more policy tightening may be necessary, resembling our scenario 2 where policy rates reach 2.5%.

In the UK, similar to the US, many workers left the labour force over the past two years; some grappling with long-term sickness, others with care-taking responsibilities, and some have emigrated as the UK left the EU. This reduction in the labour force participation rate has pushed the unemployment rate to around 50-year lows at 3.7%. Job vacancies at 1.3m is close to the total number of people unemployed, pushing wage growth to elevated levels. It remains to be seen whether workers return to the labour force, or indeed to their previous jobs, and whether the economy cools sufficiently that wage pressures ease.

Another consideration is the exchange rate. As a small open economy, UK’s interest rate differentials with the rest of the world heavily influences its inflationary dynamics via the exchange rate. The prospect of sterling depreciation is a key consideration for Catherine Mann, one of the hawkish members of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee, who has voted for a more aggressive increases in policy rates. With the US embarking on an expeditious path of policy tightening, the risk is that sterling could see further depreciation pressure if the BoE fails to match those by the Federal Reserve. This would also argue for higher policy rate settings.

Risks abound

If the past two years have taught us anything, it is to expect the unexpected. We must therefore be prepared for further economic and political shocks that could push interest rates away from our central scenario and towards a more hawkish outcome.

In the event of a complete halt in Russian supplies of gas to Europe, and further increases in the oil price, we could be faced with more difficult tradeoffs between inflation and growth. Policy makers will need to be data-dependent and nimble to adjust policy settings. Inflation prints, wage outcomes and domestic activity will be closely watched by the MPC to strike the right balance.