In the Chinese calendar, the year 2023 is the year of the rabbit, the zodiac sign which symbolises hope and luck – missing ingredients in recent economic fortunes

For almost three years after the initial outbreak of COVID in the city of Wuhan, the Chinese economy has been closed to the outside world as the authorities pursued an uncompromising Zero-Covid Policy (ZCP) to suppress infections at all economic cost. While the policy initially proved successful compared to those pursued by western countries, the arrival of effective vaccines in 2021 made it less justifiable, and 2022 saw growing citizen protests demanding its removal.

The Chinese government – typically known for its measured and well-telegraphed policy responses – surprised the world by suddenly reversing its ZCP at the end of 2022, accelerating a policy change that had been expected to play out over many months. What does this abrupt volte-face hold in store for China and the global economy, both in 2023 and in the longer-term?

Health economics

The western experience of opening up economies suggests that the initial path to normality will be rocky and dependent on health outcomes. In China’s case, the health outcomes are likely to be even more challenging. First, China’s National Health Commission recently suspended reporting of asymptomatic case counts and ceased daily releases of case numbers. Without a clear understanding of the scale of infections and where the disease is spreading, it will be difficult for people to adjust their behaviour to prevent transmission, making even higher peaks likely. By one estimate, new cases are running at 2.3m per day and are expected to peak at 4.2m by early March.1

Secondly, China’s high share of elderly population (250 million over the age of 60) and limited ICU capacity (3.6 ICU per 100,000 people vs 34.7 in US) makes its health system especially vulnerable. Vaccine hesitancy remains high, especially amongst the elderly, who are fearful of potentially tainted vaccines and have poor confidence in domestically produced vaccines. According to the World Health Organisation, only 40% of China’s over-80s have had the recommended three COVID vaccine doses.

There is also the question of the timing of China’s reopening, which is taking place during the winter flu season and the Chinese New Year holiday (21-27 January), when many people travel to see friends and relatives. Rural areas, which so far have experienced relatively low infections and have little herd immunity, are likely to be least prepared and worst affected.

The rocky road to re-opening

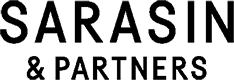

Given the significant health risks, we expect the toll on the economy from the rapid transition to reopening to be significant. During the first lockdown of 2020, GDP contracted by 10% over the quarter, and during the Shanghai lockdown of Q2 2022 GDP contracted by 2.7%

over the quarter (chart 1).

Even if the economy does not contract in Q1 2022, and only grows feebly as we expect, it remains in an exceptionally weak position. Three years of lockdown have put China on a weaker economic trajectory compared to its pre-COVID trend, with GDP 3-4 % lower than otherwise. We expect that households will greet reopening with caution and voluntarily limit their interactions, thus delaying a much-needed recovery in consumption. Retail sales in November 2022 were down almost 6% compared to a year ago, and consumers are likely to be less open-handed than usual during this year's Chinese New Year festivities.

Given the surge in sickness, production lines will struggle with absenteeism. Surveys suggest that manufacturing activity has been declining for almost six months, with demand, staffing and logistics all disrupted, and that the services industry is contracting even more sharply. Measurement issues also exist: economic data is released with a lag, and data at the start of the year is always fraught with seasonal adjustments issues as the Chinese New Year tends to fall in January or February, making annual comparisons and interpretations difficult.

Hope springs

After the spring and peak infections, revenge spending is likely to dominate. Household consumption will accelerate as people spend their lockdown savings, and experience-deprived households will shift to services spending. With demand picking up and supply constraints in production easing, it is unclear whether domestic inflationary pressures will mount as they did in western countries. Consumer price inflation is currently below 2%, and labour supply is plentiful, with the official urban unemployment rate at around 5.5%, but in reality is probably substantially higher given reported wage falls of 10-20%. Unemployment is likely to be much higher in rural areas, which are not included in the official statistics. If workers who lost their jobs return to their posts quickly, this could steady the economic transition and reduce the risk of mis-matched jobs and skills – one of the key labour market issues currently faced in Europe and the US.

Additionally, the crisis in the property market – driven by both lockdowns and government regulatory policy – appears to be near its trough. In November, the government eased property developers’ access to financing, and more recent communication suggests that policy in 2023 will be supporting ‘fundamental demand’ such as from first-time home buyers. This could mean lower mortgage rates and changes to down-payments.

We are hopeful that, after a painful start, the remainder of 2023 will be a year of economic recovery that could see GDP growth rebound from an expected meagre 3% in 2022 to around 5% in 2023. For this to happen, the drivers of China’s economic growth will need to rotate and the economy to rely less on government infrastructure spending and exports, and focus on a more sustainable and resilient source – household consumption.

What does this mean for the rest of the world?

As the world’s second-largest economy and contributing one-third of global economic growth in typical years, China’s economic rebound will cause significant spill-overs internationally. Given China’s outsized share of global consumption, one key transmission channel will be commodity markets. While commodity-producing countries like Brazil, Chile and Australia stand to benefit, importers will struggle. For Europe, which is desperately substituting away from Russian natural gas, a resurgent China could mean greater competition for limited LNG imports, resulting in a shortfall of 27bn cubic metres of gas (equivalent to 7% of its annual consumption) and the prospect of energy rationing in 2023.2 Similarly, greater Chinese oil imports could push global oil prices higher, with analyst estimates suggesting a boost of as much as US$15 per barrel that would see Brent crude prices return to US$100 per barrel. In a world facing double-digit inflation and on the precipice of recession, this added inflationary impulse would be a difficult for many economies to absorb.

The other key transmission channel is likely to be via tourism exports. Pent-up demand by China’s vast middle class – which once accounted for almost 20% of international tourism spending – is likely to benefit nearby Asian countries like Hong Kong and Thailand. However, this channel may take longer to play out, as many countries have recently announced Covid test requirements for Chinese tourists, weighing the benefits of Chinese spending against the risk of importing Covid.

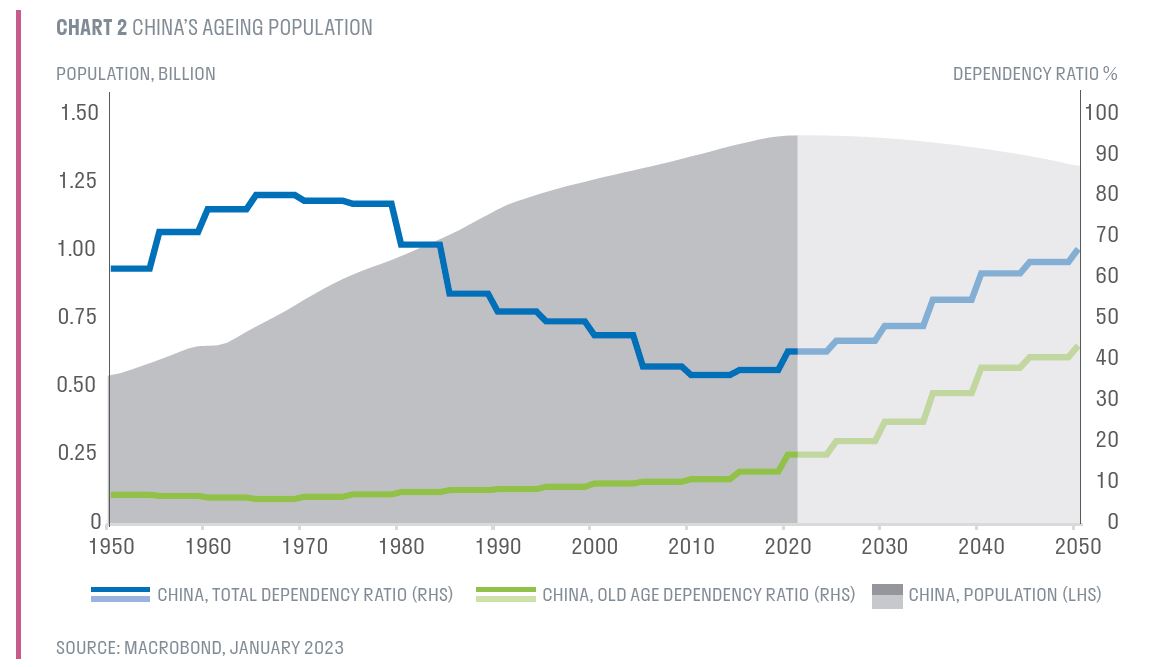

Longer-term projections are hard to make, but some observations are possible. China already faced significant growth challenges in the medium term due to poor demographics. The old-age dependency ratio is expected to rise from around 17% today to 43% by 2050, according to the UN (chart 2). This will be a significant strain on China’s growth prospects and its contribution to global growth.

As production lines normalise and supply chains heal, the re-opening of the economy is likely to reveal permanent scars. The young who missed out on vital education during the three Covid years may face difficulties in training and integrating into the labour market.

Meanwhile, foreign investors, given their aversion to policy uncertainty, are likely to have relocated operations to alternative destinations, leaving a void that is unlikely to be filled quickly. Perhaps most important of all, is whether confidence and credibility in the government’s leadership has been damaged as President Xi begins his third term in office. He may be hoping for some good rabbit luck.

Important Information

This document is for investment professionals in the US only and should not be relied upon by private investors. If you are a private investor, you should not act or rely on this document but should contact your professional advisor.

The information on which the document is based has been obtained from sources that we believe to be reliable, and in good faith, but we have not independently verifi ed such information and no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy. All expressions of opinion are subject to change without notice.

US Persons are able to invest in units or shares of Sarasin & Partners LLP funds if they hold qualified investor status and enter into a fully discretionary investment management agreement with Sarasin Asset Management Limited. US persons are U.S. taxpayers, nationals, citizens or persons resident in the US or partnerships or corporations organized under the laws of the US or any state, territory or possession thereof.

This document has been prepared by Sarasin & Partners LLP (“S&P”), a limited liability partnership registered in England and Wales with registered number OC329859, authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and approved by Sarasin Asset Management Limited (“SAM”), a limited liability company registered in England and Wales with company registration number 01497670, which is authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and registered as an investment adviser with the US. The information in this document has not been approved or verified by the United States Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) or by any state securities authority. Registration with the SEC does not imply a certain level of skill or training.

Please note that the prices of shares and the income from them can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested. This can be as a result of market movements and also of variations in the exchange rates between currencies. Past performance is not a guide to future returns and may not be repeated. Management fees and expenses are described in SAM’s Form ADV, which is available upon request or at the SEC's public disclosure website, https://www.adviserinfo. sec.gov/Firm/115788.

For your protection, telephone calls may be recorded. SAM and/ or any other member of Bank J. Safra Sarasin Ltd. accepts no liability or responsibility whatsoever for any consequential loss of any kind arising out of the use of this document or any part of its contents. The use of this document should not be regarded as a substitute for the exercise by the recipient of his or her own judgment. SAM and/or any person connected to it may act upon or make use of the material referred to herein and/or any of the information upon which it is based, prior to publication of this document.

©2023 Sarasin Asset Management Limited – all rights reserved. This document can only be distributed or reproduced with permission from Sarasin Asset Management Ltd.