Key points:

- Nowhere is US power more visible than in the dominance of the dollar, which accounts for more than half of global foreign exchange reserves.

- The Trump administration believes that a strong dollar has led to domestic and global economic imbalances with trading partners pursuing policies that have perpetuated chronic trade deficits.

- We expect that the dominance of the dollar – long underpinned by trust in the US as a responsible steward – will erode over time.

As the Cold War drew to a close in the early 1990s, the United States set out to cement its global leadership. With the USSR collapsing and China only beginning to look outward, the US stood as the world’s unrivalled military, financial and economic superpower. Over the next three decades, both Democratic and Republican administrations worked through multilateral institutions to exert America’s influence as a benign hegemon – assertive, yet broadly cooperative – underwriting the global order while reaping the benefits of an increasingly interconnected world.

Nowhere is American power more visible than in the dominance of the dollar. Though the US economy represents roughly 25% of global GDP, the dollar accounts for 57% of official foreign exchange reserves and 54% of global export invoicing, and is used in 60% of cross-border loans.[1] Around 70% of global bond issuance is denominated in dollars, as is 88% of currency trading.[2] In virtually every corner of global finance, the greenback reigns supreme.

Dollar dominance confers a host of strategic advantages on the US. It reduces friction for firms operating overseas, grants policymakers rare insight into global financial flows, and provides a potent tool for imposing sanctions with extraterritorial reach. But the greatest benefit lies in the dollar’s role as the world’s dominant reserve currency. Unlike other nations, the US need not stockpile foreign reserves to guard against depreciation of its own currency. Instead, the rest of the world holds dollars – creating a built-in global market for American debt that affords the US extraordinary monetary and fiscal latitude.

An inward pivot

Under Donald Trump, the US is abandoning its long-standing role as a benign hegemon. The administration argues that the US ceded too much authority to multilateral institutions, compromising its own strategic interests. In response, it has actively withdrawn support from institutions such as NATO, the UN, the WTO and the WHO, while recasting its trade relationships on tougher, more unilateral terms.

What has emerged is a wholesale redefinition of America’s global posture: from rule-setting guarantor to transactional hegemon – wielding its economic, financial and military muscle to secure bilateral concessions, one deal at a time.

Alongside a more transactional view of the world, sits a more circumspect view of the dollar’s role in the global economy. Team Trump believes that a strong dollar has been a key driver of both domestic and global economic imbalances. The administration believes that America’s trading partners have been pursuing policies that suppress wages, undervalue their currencies and provide industrial subsidies that have perpetuated chronic trade deficits. The implications for the dollar are nuanced, and arguably conflicting – while the Trump administration widely accepts that the dollar’s reserve currency status is an ‘exorbitant privilege’, the administration simultaneously views the dollar’s strength as an ‘exorbitant burden’ which has hollowed out the country’s manufacturing base, led to ‘excessive financialisation’ of the economy, increased inequality and facilitated excessive government borrowing.

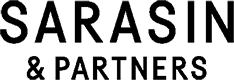

US claims that the dollar’s overvaluation is the result of mercantilist policies of its trading partners are not without merit. Since joining the WTO, China has deliberately maintained an undervalued exchange rate to cement its position as the world’s manufacturing powerhouse. Given its central role in the broader Asian supply chain, the weak renminbi has exerted downward pressure on the currencies of neighbouring economies as well. The net effect is that the trade-weighted dollar now stands more than two standard deviations above estimates of fair value – a level of misalignment that has played a meaningful role in America’s ballooning trade deficits (chart 2.1).

The administration has made its goals plain: it aims to rebalance the economy away from chronic trade deficits, revive domestic manufacturing, and plug a two trillion-dollar fiscal deficit [3] – largely through the catch-all instruments of tariffs and currency depreciation. All the while, it seeks to preserve the benefits of the dollar’s privileged status as the world’s reserve currency.

Tariffs – a forever tool?

Three months on from the “shock and awe” of President Trump’s Liberation Day tariff announcement, confusion still reigns over the policy’s endgame. What is taking shape, however, are the broad contours of a two-tiered tariff regime. Tier one imposes a flat 10% tariff on all imports, effectively functioning as a toll on foreign manufacturers seeking access to the vast American consumer market. Its primary objective is revenue generation. Tier two consists of targeted tariffs, selectively applied to countries and sectors. These are designed to shield strategic domestic

industries, extract concessions from trading partners, or penalise geopolitical adversaries. Together, the system seeks to advance Mr. Trump’s protectionist ambitions while raising fiscal revenue.

Tariffs have already started to deliver meaningful fiscal dividends. For the month of June, tariff revenues came in at $28bn which amounts to about $330bn on an annualised basis or 17% of the $2trn in deficits expected over the next couple of years.[4] Over time, countries and companies will start to adjust their behaviour; transhipping goods through more favourable tariff regions and shifting production to the US, chipping away some of the revenue benefits.

The greater challenge is that tariffs, once considered relics of a failed era, are fast becoming a permanent instrument of statecraft. Yet, there is little certainty that tariff rates, once imposed, will remain stable and predictable – the ability to adjust rates up or down to reflect evolving international

relationships is why they are seen as an attractive tool. This persistent ambiguity is likely to further fragment global trade and accelerate the localisation of supply chains.

Over time, this will raise costs, reduce efficiency and erode competitiveness. Nonetheless, the US objective of reducing trade deficits may gradually materialise, as households and businesses adapt their consumption and sourcing patterns in response to the new tariff landscape.

Will the kindness of strangers continue to plug the deficit gap?

A salient feature of America’s chronic trade deficits has been the emergence of US Treasury bonds as the world’s pre-eminent safe asset. As America’s trading partners accumulated trade surpluses, they recycled them into US government debt. Deep and liquid markets for Treasuries, coupled with the Federal Reserve’s demonstrated willingness to supply dollar liquidity in times of global stress, made them a natural home for foreign exchange reserves. After all, the US was a benign global hegemon, trusted to safeguard global finance.

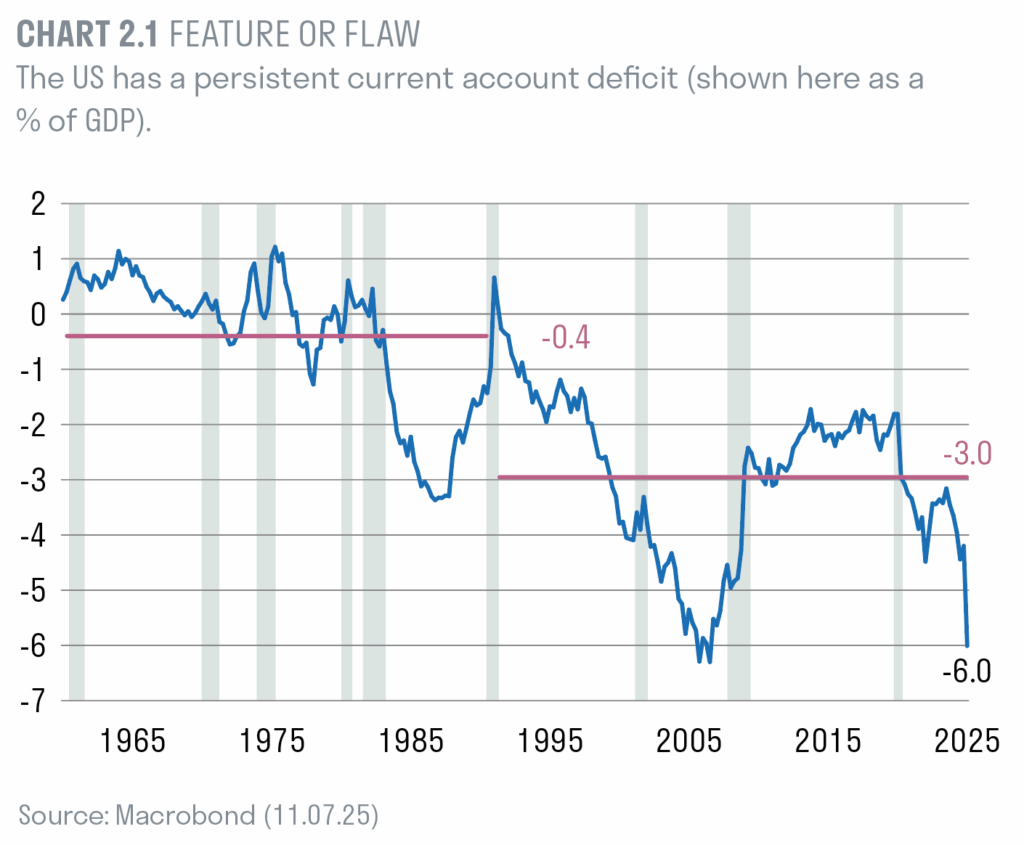

Looking forward, foreign appetite for US Treasuries is likely to wane. As global trade increasingly re-orients away from the US, fewer dollars are being accumulated abroad. Meanwhile, Washington’s liberal use of sanctions and tariffs has put much of the emerging world on edge. Many emerging markets are actively allocating to gold in lieu of Treasuries (chart 2.2). Compounding the unease is background chatter in Washington about taxing interest income on Treasuries or forcibly extending the maturity of existing holdings – measures that are steadily eroding confidence in the asset class.

Foreign investors face an additional headwind: America’s deteriorating fiscal outlook. The recent passage of the 'One Big Beautiful Bill Act' worsens an already poor fiscal trajectory.

Deficits are now expected to reach 7% over the remainder of President Trump’s term while debt levels are expected to reach 130% of GDP over the next decade.5 With neither party showing much appetite for raising taxes or cutting spending, the likely policy path involves a mix of higher inflation and prolonged interest rate suppression. For long-term foreign investors, this raises the risk of inflation eroding the capital value of their Treasury holdings. An overvalued dollar together with a diminishing appetite to hold US Treasuries will lead to a gradual erosion of the dollar’s value against its main trading partners.

A hegemonic shift

After decades of overseeing the global order as a benign hegemon, the US is charting a new course as a transactional and extractive power. No longer content to underwrite multilateralism, Washington is seeking to maximise its leverage, using access to its economy and financial system to extract concessions. This pivot marks a decisive break from the globalised era of the past three decades and will reshape the architecture of trade and finance in meaningful ways.

As the world fragments, countries are likely to turn inward, supply chains are likely to localise, and markets are likely to become more regional. In this new landscape, global bond markets will come under pressure, strained by America’s unrestrained fiscal profligacy and the growing need to finance domestic priorities elsewhere. Meanwhile, the dominance of the dollar – long underpinned by trust in the US as a responsible steward – will erode over a multi-year period. Foreign investors are increasingly reassessing the risks of holding the liabilities of an unreliable partner running unsustainable fiscal policies.

In this multipolar world, businesses aligned with national strategic priorities – those in resources, defence, and cybersecurity – stand to gain. As globalisation recedes and geopolitics returns to the fore, economic advantage will accrue not just to the most efficient, but also to the most secure.

[1] https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-changing-roleof-the-us-dollar/

[2]https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/content-series/atlantic-councilstrategy-paper-series/why-the-us-cannot-afford-to-losedollar-dominance

[3] 3 https://bipartisanpolicy.org/report/deficit-tracker/

[4] Treasury Daily Statement, US Treasury Department and Macrobond

[5] https://www.ft.com/content/7eca7746-79a4-4eef-92ce-a63f71be58b7

Important information

This document is intended for retail investors and/or private clients in the US only. You should not act or rely on this document but should contact your professional adviser.

This document has been prepared by Sarasin & Partners LLP (“S&P”), a limited liability partnership registered in England and Wales with registered number OC329859, which is authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority with firm reference number 475111 and approved by Sarasin Asset Management Limited (“SAM”), a limited liability company registered in England and Wales with company registration number 01497670, which is authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority with firm reference number 163584 and registered as an Investment Adviser with the US Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. The information in this document has not been approved or verified by the SEC or by any state securities authority. Registration with the SEC does not imply a certain level of skill or training.

In rendering investment advisory services, SAM may use the resources of its affiliate, S&P, an SEC Exempt Reporting Adviser. S&P is a London-based specialist investment manager. SAM has entered into a Memorandum of Understanding (“MOU”) with S&P to provide advisory resources to clients of SAM. To the extent that S&P provides advisory services in relation to any US clients of SAM pursuant to the MOU, S&P will be subject to the supervision of SAM. S&P and any of its respective employees who provide services to clients of SAM are considered under the MOU to be “associated persons” as defined in the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. S&P manages mutual funds in which SAM may invest its clients’ assets as appropriate. To the extent that SAM is able to exercise proxy voting on behalf of its clients, SAM follows the policy set by S&P. Proxy voting is an operational process dependent upon support from SAM’s clients’ custodians, some of which do not support proxy voting in all or certain markets.

This document has been prepared for marketing and information purposes only and is not a solicitation, or an offer to buy or sell any security. The information on which the material is based has been obtained in good faith, from sources that we believe to be reliable, but we have not independently verified such information and we make no representation or warranty, express or implied, as to its accuracy. All expressions of opinion are subject to change without notice.

This document should not be relied on for accounting, legal or tax advice, or investment recommendations. Reliance should not be placed on the views and information in this material when taking individual investment and/or strategic decisions.

The value of investments and any income derived from them can fall as well as rise and investors may not get back the amount originally invested. If investing in foreign currencies, the return in the investor’s reference currency may increase or decrease as a result of currency fluctuations. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results and may not be repeated. Forecasts are not a reliable indicator of future performance. Management fees and expenses are described in SAM’s Form ADV, which is available upon request or at the SEC’s public disclosure website, https://www.adviserinfo.sec.gov/Firm/115788.

Neither Sarasin & Partners LLP, Sarasin Asset Management Limited nor any other member of the J. Safra Sarasin Holding Ltd group accepts any liability or responsibility whatsoever for any consequential loss of any kind arising out of the use of this document or any part of its contents. The use of this document should not be regarded as a substitute for the exercise by the recipient of their own judgement.

Where the data in this document comes partially from third-party sources the accuracy, completeness or correctness of the information contained in this publication is not guaranteed, and third-party data is provided without any warranties of any kind. Sarasin & Partners LLP shall have no liability in connection with third-party data.

© 2025 Sarasin Asset Management Limited – all rights reserved. This document can only be distributed or reproduced with permission from Sarasin Asset Management Limited. Please contact marketing@sarasin.co.uk.