This month, indeed this year, has all been about politics, with almost half the global population voting in more than 70 elections across the world[1]. Last week in the UK saw Labour’s first victory from opposition in 27 years, a high-wire French parliamentary election and a pivotal debate over whether the American president is fit enough to run for a second term.

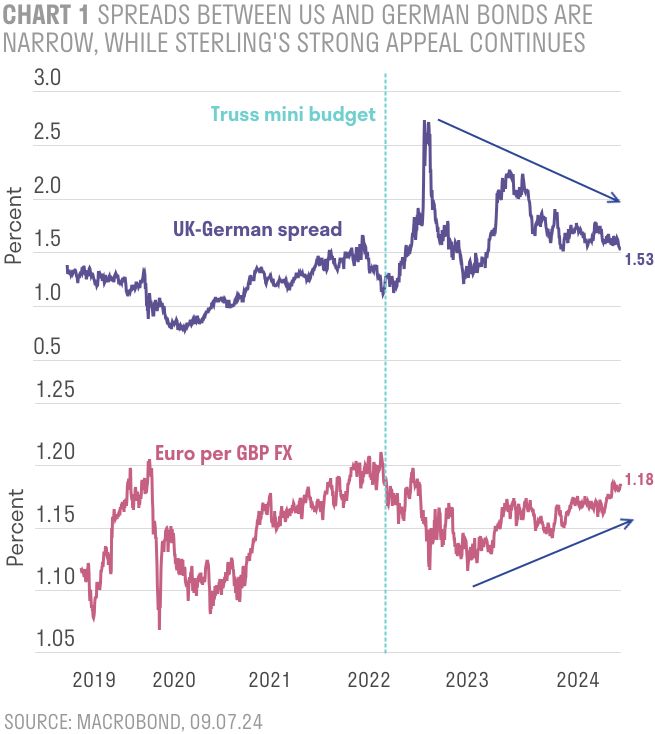

Running through all of these events has been one dominant thread – namely, rising public debt levels. International Monetary Fund (IMF) figures now show that global public debt is almost 9% above pre-pandemic levels, with only half of world economies managing to tighten fiscal policy at all last year. The US, for example, has been recovering strongly but the budget deficit is still likely to reach $2 trillion this year (or 6.5% of GDP) – a level one might more normally have expected to witness during times of national crisis.

Confronting the debt pile

Politicians in the US, France and the UK are all facing their debt challenges in different ways. In the US, neither presidential candidate seems willing to talk about public indebtedness – the Republicans believe in extending tax cuts, while the Democrats advocate for continued federal government spending programmes.

In France, the surprise parliamentary success of the French left (New Popular Front) but with no one party dominant, is probably the least bad outcome for the economy. A far-right government has been avoided while President Macron’s party has not been wiped out. Nevertheless, NPF policy still includes a 10% pay rise for civil servants, lowering the retirement age from 64 to 60, and enhancing social welfare programs. In short, any coalition government will almost certainly struggle to deliver on fiscal consolidation.

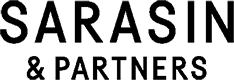

Perhaps surprisingly, it is the UK that is showing the first signs of a willingness to address deficits. This is partly due to the lingering impact of Prime Minister Truss’s disastrous mini-budget of September 2022. The swift policy reversal it necessitated demonstrated the bond markets’ power to enforce fiscal discipline, even when governments refuse to act themselves. The Labour Party’s 2024 manifesto reflects this shift in thinking, prioritising 'economic stability with tough spending rules' as its foremost objective. This marks a truly remarkable reversal from the strident tax-and-spend approach of Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour party (which included Keir Starmer), a little more than four years ago.

Is the UK under Starmer really a financial safe-haven?

Chancellor Rachel Reeves made the unexpected decision some months ago to go to the polls with a near-duplicate of Conservative economic policy, and the gamble appears to have paid off. Labour has promised no rises in income taxes, VAT or National Insurance, alongside a commitment to cap corporation tax at today’s 25 percent. They also committed to maintaining the same Conservative target for national debt, falling as a percentage of GDP in the fifth year of a new parliament, alongside tight spending controls that are comparatively well costed.

Financial markets have responded positively: sterling has strengthened against the euro for much of this year, and last month witnessed one of the most heavily over-subscribed gilt issues in recent British history. The UK equity market also appears to have started a gradual re-rating, outperforming other major indices over the last three months. While part of this financial stability can be credited to former Prime Minister Sunak's efforts, particularly his Windsor Framework with Europe, indications suggest that this new Labour administration will maintain a fiscally conservative stance.

French debt was on an unsustainable path even before the vote

The French spending programmes outlined by both the far right and left parties are significantly larger than anything even Liz Truss proposed. With an expected deficit of 5% of GDP in 2024 and debt at around 111% of GDP, France is already facing severely strained public finances.

Following last weekend's parliamentary elections, far-left leader Jean-Luc Mélenchon has told supporters he wants to form a government and implement a large fiscal programme. While a far-left government of this sort is unlikely, unless a tough technical administration is appointed, France’s bond market could still, over time, start to resemble Italy’s. With a debt-to-GDP ratio now at 111% – the third largest in Europe after Greece and Italy – the country could face permanently higher borrowing costs and risk becoming a potential flashpoint during the next Euro-bloc crisis.

Both parties in the US seem to be in denial over the soaring US deficit

Despite warnings from the Congressional Budget Office that US debt-to-GDP ratios could soon surpass World War II highs, the issue of managing this debt is notably absent from both parties' campaign rhetoric. Under a Trump administration, large parts of the 2017 tax cuts would likely be extended, reducing projected federal revenues by nearly $4 trillion over the next decade. Yes, Trump has talked of implementing universal tariffs that might raise revenues, but this remains wholly untested.

Biden is also a spender; the Congressional Budget Office estimates that the US deficit will still be 6.9% of GDP in 2034, significantly higher than the 3.7% average over the past 50 years.

The key role of the US dollar in the global financial system provides America extraordinary latitude to continue deficit spending in ways other countries cannot (the so-called Exorbitant Privilege). However, as interest costs rise alongside higher spending, so will the deficit. This will likely increase bond yields and borrowing costs. In the next US recession, government deficits could plausibly widen by another 4%, pushing the annual deficit to over 10%. In this scenario, bond yields could rise (instead of falling, as typically occurs during a slowdown) potentially triggering a full-blown funding crisis – a scenario not inconceivable even for the giant US bond market.

So, what does this mean for investors today? How should portfolios be constructed to mitigate the risks involved in an eventual de-leveraging process?

- Diversify into private assets: The extraordinary rally in US growth stocks, particularly the winners from the Artificial Intelligence (AI) revolution, has been largely driven by their robust cash flows. These companies have strong balance sheets, meaning rising interest rates can actually boost their earnings – the opposite of what indebted national governments face. By contrast, valuations of smaller, publicly listed companies have languished and private market participants are increasingly buying up, consolidating and harvesting value in this market. Looking ahead, investors will not only need to be nimble about the concentration risks in the market, but also expand their opportunity set to include private markets.

- Natural buyers for fixed interest investments: Ensure there are natural buyers when holding fixed interest investments. UK corporate debt presents an opportunity, attracting steady, multi-year flows from UK pensions. As defined-benefit salary schemes in the UK move from deficit to surplus (thanks to normalised interest rates), many companies are approaching bulk annuity providers to offload risk.

With UK investment-grade credit yielding close to 5.5%, these insurance companies should become natural buyers as UK inflation likely stabilises around 2-2.5%. Selected UK infrastructure opportunities (absent excessive gearing) offer similar advantages for investors, supported by Labour’s pro-growth agenda.

- Strategic position in gold: Continue to hold a strategic position in gold due to the uncertainty surrounding how governments will confront their deficits. Western economies might emulate Japan, by continually expanding public debt, but this requires a large trade surplus and a deep pool of domestic investors willing to accept low returns.

More likely, the ‘bond market vigilantes’ that ousted PM Truss and her chancellor will reappear. They showed their power in the French bond market last month and may force fiscal adjustments on the US government as well. Thus, gold remains a hedge against a more abrupt adjustment in government borrowing.

- Tilt equity portfolios to strategic themes: Focus equity portfolios on themes that require significant investment from both the government and private sector. These include decarbonisation and electrification across various industries, healthcare for an ageing population, as well as heightened defence and security challenges. AI will continue to evolve – so far, the focus has been on the industry's 'picks and shovels' (semiconductor stocks), but as business models change, capital-light industries will emerge that require little debt funding.

Confronting global debt levels was never going to be easy for a generation of politicians accustomed to deploying vast fiscal programmes to cushion every economic crisis, as my colleague Adam Hamilton points out in his article, 'Government borrowing: the winners and losers'. Government support following the 2008 financial crisis, the pandemic, and the recent Russian energy shock has collectively caused the US debt pile to double since 2008, after remaining broadly stable for the previous 30 years. The long journey back to fiscal stability is only now beginning, and it will be full of risks as well as opportunities. For once, the UK may be at the forefront of this effort.

[1] 2024 is the biggest election year in history, The Economist, November 2023

This document is intended for retail investors in the US only. You should not act or rely on this document but should contact your professional adviser.

This document has been prepared by Sarasin & Partners LLP (“S&P”), a limited liability partnership registered in England and Wales with registered number OC329859, which is authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority with firm reference number 475111 and approved by Sarasin Asset Management Limited (“SAM”), a limited liability company registered in England and Wales with company registration number 01497670, which is authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority with firm reference number 163584 and registered as an Investment Adviser with the US Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. The information in this document has not been approved or verified by the SEC or by any state securities authority. Registration with the SEC does not imply a certain level of skill or training.

In rendering investment advisory services, SAM may use the resources of its affiliate, S&P, an SEC Exempt Reporting Adviser. S&P is a London-based specialist investment manager. SAM has entered into a Memorandum of Understanding (“MOU”) with S&P to provide advisory resources to clients of SAM. To the extent that S&P provides advisory services in relation to any US clients of SAM pursuant to the MOU, S&P will be subject to the supervision of SAM. S&P and any of its respective employees who provide services to clients of SAM are considered under the MOU to be “associated persons” as defined in the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. S&P manages mutual funds in which SAM may invest its clients’ assets as appropriate.

This document has been prepared for marketing and information purposes only and is not a solicitation, or an offer to buy or sell any security. The information on which the material is based has been obtained in good faith, from sources that we believe to be reliable, but we have not independently verified such information and we make no representation or warranty, express or implied, as to its accuracy. All expressions of opinion are subject to change without notice.

This document should not be relied on for accounting, legal or tax advice, or investment recommendations. Reliance should not be placed on the views and information in this material when taking individual investment and/or strategic decisions.

The value of investments and any income derived from them can fall as well as rise and investors may not get back the amount originally invested. If investing in foreign currencies, the return in the investor’s reference currency may increase or decrease as a result of currency fluctuations. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results and may not be repeated. Forecasts are not a reliable indicator of future performance. Management fees and expenses are described in SAM’s Form ADV, which is available upon request or at the SEC’s public disclosure website, https://www.adviserinfo.sec.gov/Firm/115788.

Neither Sarasin & Partners LLP, Sarasin Asset Management Limited nor any other member of the J. Safra Sarasin Holding Ltd group accepts any liability or responsibility whatsoever for any consequential loss of any kind arising out of the use of this document or any part of its contents. The use of this document should not be regarded as a substitute for the exercise by the recipient of their own judgement.

The index data referenced is the property of third-party providers and has been licensed for use by us. Our Third-Party Suppliers accept no liability in connection with its use. See our website for a full copy of the index disclaimers https:// sarasinandpartners.com/important-information/.

Where the data in this document comes partially from third-party sources the accuracy, completeness or correctness of the information contained in this publication is not guaranteed, and third-party data is provided without any warranties of any kind. Sarasin & Partners LLP shall have no liability in connection with third-party data.

© 2024 Sarasin Asset Management Limited – all rights reserved. This document can only be distributed or reproduced with permission from Sarasin Asset Management Limited. Please contact marketing@sarasin.co.uk.