Issuing government bonds linked to re-wilded land could create massive environmental benefits

“We must respond to the call of the forest,” said President Macron of France at the close of the August 2019 G7 summit.

Set against such powerful rhetoric from many world leaders on the need for action on biodiversity loss and climate change, the G7 pledge of €20 million to help fight forest fires in the Amazon seemed to many a bewilderingly small sum.

Ahead of the summit, the IPCC published a Special Report on Climate Change and Land providing governments with a thorough scientific analysis of global land use and another stark warning of the immediate need to radically change human behaviour to halt further climate damage.

Land-use change causes a quarter of man-made emissions. Substantial alterations are required to agriculture and timber management to reverse land degradation, desertification and carbon emissions. The report further amplifies the ‘tragedy of the commons’ laid out by the IPBES in their May 2019 Global Assessment on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services . This described how “the loss of species, ecosystems and genetic diversity is already a global and generational threat to human well-being”.

These thorough scientific reports on land use suggest a serious high-level reappraisal is required of how humanity considers and manages the earth’s land resources. The output the world needs from land today is not just monoculture grain production on an excessive scale, but carbon absorption and biodiversity.

Policy makers have an extraordinary historic opportunity to initiate massive change to land use at a time when a set of other circumstances in the wider world may help significantly with implementing it – record low bond yields, changing technology and a new public environmental awareness all support policy change.

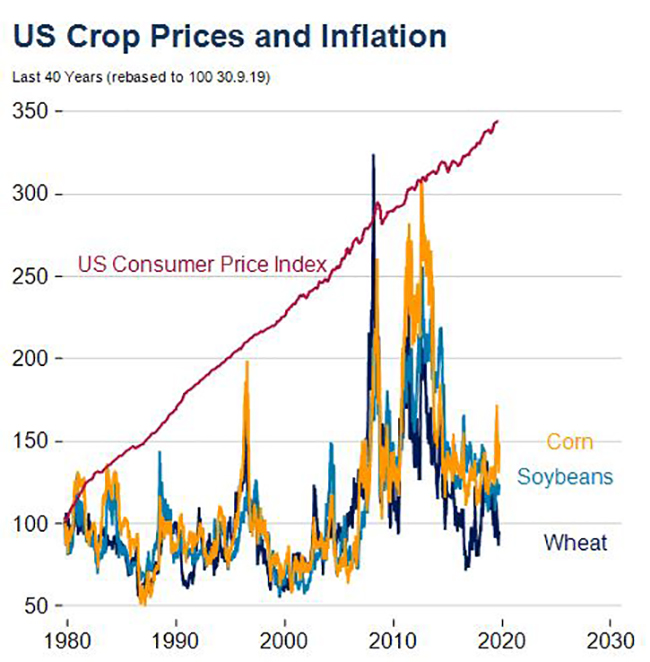

Part of the reason we find ourselves with this seeming conflict between land use and climate change is that current economic structures have encouraged the conversion of natural capital into financial capital. The result has been that a high proportion of viable land has been cleared for agriculture. While much of this has been rationalised by the inbuilt instinct of national leaders to keep food prices low and create national food security, the reality is that supply of grains now greatly exceeds natural food demand. Over the course of the twentieth century, mechanisation, hybrid seeds and intensive chemical use allowed crop yields to increase by three or four times.

However, over the last 20 years, government policies on biofuels – combustion fuels derived from calories in plants – have compounded ecological damage. By subsidising and mandating the use of crops for biofuels, governments hoped to create additional demand in an attempt to support agricultural crop prices, which have struggled to keep up with inflation in recent years (Figure 1). But biofuels contributed to land-use change. Previously unspoilt forest and grasslands have been cleared to grow biofuels or replace the food crops that were diverted for biofuel production elsewhere.

The lack of environmental logic inherent in biofuel policies that contribute to land-use change would appear to make them an easy first step for reform. Yet, there is a risk that removing these and other agricultural subsidies would have a significant impact on rural economies. Grain prices would almost certainly drop and so would land prices. Perhaps the answer is instead to change the policies to support the rural population in other ways.

The UK is among several governments contemplating paying subsidies for ‘public goods’ such as environmental enhancement, rather than for over-production of crops. This could be taken a step further to include explicit control of land supply. If governments were to buy agricultural land from farmers at a set price, it could be retired from agricultural use and re-wilded to provide the environmental public goods required. From the farmer’s perspective, the capital would allow the repayment of loans and support the injection of capital into rural economies, helping to buffer the loss of income from lower crop prices as price support mechanisms are withdrawn.

What would governments then do with the land? This is where creative thinking is required. At the same time as society begins to recognise the environmental crisis it faces, in the financial world interest rates have plunged close to zero. Indeed, trillions of dollars’ worth of government bonds now offer negative yields. This leaves long-term savings institutions such as pension funds, insurance companies and endowments with nowhere to invest safely and still earn even a small return. Potentially there could be huge demand for a secure asset that can provide a better yielding substitute to conventional government bonds, particularly in Europe and Japan.

The green bond market is already established – as of October 2019, several tens of billions of dollars of green bonds have been issued, with a range of environmental projects financed by the proceeds. But only a small proportion relate to land use and this is just one leaf in the forest compared with the true scale required.

‘Eden bonds’ would be a new class of government bonds with the ability to revert land to a natural state. They would be issued to investors on a long-term basis but structured as a lease on a parcel of re-wilded land. That land will then be repurchased by the government at a ‘gilt-edged’ fixed price in, say, 50 years. In the meantime, the government pays a small interest rate for the guarantee that the land remains uncultivated and that a local workforce is employed to manage the transition back to the wild and to police it. The holder of these ‘Eden bonds’ could even earn additional income by selling carbon credits and credits for providing other public goods, including the restoration of populations of endangered species. The holder of an Eden bond has to work harder for their return, but it will be a higher return than on a conventional government bond.

The Paris Climate Agreement of 2015 set out three long-term goals: the first is to limit global average temperature rise, and the second is to increase the ability to adapt to climate impacts. The IPCC Land report highlights that without extraordinary changes to the way in which land is utilised, neither of those first two goals will be met.

What is also clear is that changes to the way in which land is utilised will only come if the third (and oft-overlooked) long-term goal is met. The Paris Agreement also committed to make “finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development”. Given high demand for secure, positive-yielding assets, policymakers now have the opportunity to transform our approach to land use by aligning financial flows with urgently needed climate stabilisation objectives.