Sharp rises in interest rates are taking their toll on the banking sector, which could cause central banks to delay further rises while they assess the damage. This is not a time for bravery in portfolio construction: we maintain a modest underweight to global equities.

After the Financial Crisis of 2008, the world economy struggled with tepid growth and weak inflationary pressures. Central banks responded by pursuing skewed policies: they were quick to cut interest rates aggressively if the economy slowed and slow to raise them when the economy strengthened. Underpinning this was a belief that inflation was much easier to cure than deflation, particularly in a world laden with crisis-era debt. Go early, go hard has been the policymakers’ mantra and financial markets have cheered from the sidelines.

The post-Covid economy has turned this doctrine on its head. Ample fiscal support, discombobulated supply chains, the war in Ukraine, a burgeoning cold war with China, headwinds from ageing demographics in developed economies and climate change have scrambled supply and demand like never before. The result has been a surge in inflation that surprised policymakers.

In the US, the Federal Reserve has raised interest rates by 4.5% in just under a year1 – an unprecedented pace. Headline inflation has dropped from a recent peak of 9.1% to 6.0% in February2 and should continue to decline as year-on-year comparisons for food and energy prices become less demanding. However, labour markets remain an obvious concern at this point and the Federal Reserve will want to see clear indications of slowing wage growth before relieving interest rate pressure.

Raising rates ‘til something breaks

A resilient economy – one that exhibits low sensitivity to interest rates – was always going to be a challenge for the Federal Reserve because its key policy tool is less effective for cooling down an overheated economy. With every increase in interest rates, the risk that something within the financial system breaks only rises. A decade of ultra-low interest rates has almost certainly led to investor complacency or mispricing of long-term risk.

Over the past year, examples of financial fragility have come to light: the implosion of the crypto industry following the collapse of a leading exchange, FTX, and closer to home, volatility in bond yields caused by the ill-advised ‘mini-budget’ under former PM Liz Truss.

With contagion into the broader financial system from these earlier implosions seemingly contained, the Federal Reserve and other global central banks continued to march rates higher. Last week, however, concerns about the robustness of the banking system spread across both coasts of America.

Buckling under the pressure

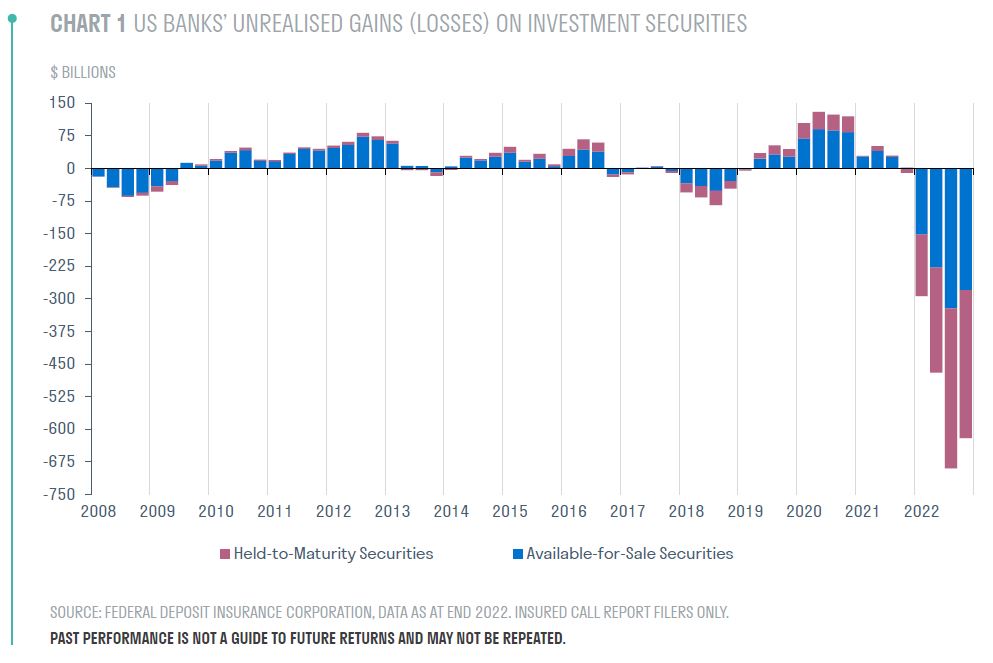

Rising interest rates reduce the value of most financial assets, as future cashflows are discounted back to the present at a higher rate. This is true even for assets with no credit risk, like the safe, government-backed investment securities held by the banking sector. As a result, even though the expected cashflows from these assets hasn’t changed, the sharp move in interest rates over the past year has generated an extraordinary US$600bn+ loss in the marked-to-market value of the US banking system’s investments3.

At over US$2tn, the combined equity of the banking system can swallow losses of this magnitude, but the exposures are not evenly distributed. SVB Group, a bank focused on the venture technology industry, went into receivership on 10 March alongside the smaller Signature Bank, as concerns around their balance sheet hedging quickly morphed into depositor withdrawals and solvency issues. This sparked a global sell-off in bank shares as investors worried about who might be next – with the much larger Credit Suisse quickly becoming the focus of market concerns.

You break it, you own it

The US regulators swiftly announced a range of measures to contain this crisis, most notably a guarantee for all deposits at the banks in receivership, and a new temporary lending programme that allows banks to borrow from the Federal Reserve using the par value of their investments as collateral. In the UK, the Bank of England hastily arranged for HSBC to purchase the UK arm of SVB for a nominal £14, while the Swiss National Bank has provided an emergency loan of c.£44bn to Credit Suisse, the most troubled European lender5.

All potential interventions come with material drawbacks, but in reality regulators have no choice but to intervene. In the modern world, bank runs can move with astonishing speed, and a disorderly failure of a major bank would affect far more than just the direct depositors.

What comes next?

If the banking sector’s problems continue to spread and contagion risks begin to rise, central banks will not shy away from resuming quantitative easing, or even cutting interest rates to quell the panic. With the lessons learned from previous banking crises and the potential for interest rate cuts to mitigate the problem of marked-to-market losses on bank balance sheets, it looks likely that central banks have the tools and the know-how to manage the immediate crisis.

As central banks sit down to set policy over the next week, there is a wide range of possible outcomes. Given the high degree of uncertainty, the most prudent approach may be to pause and assess the damage to the economy. The well-publicised concerns around broad swathes of the banking sector can cause a material tightening in financial conditions through tighter lending standards, more conservative balance sheet management and even unemployment if significant parts of the real economy are sufficiently impacted, which in turn would significantly reduce inflationary pressure in the economy. If financial conditions stabilise and bank lending remains relatively strong, central banks could resume their hiking cycle.

Some central banks may feel that, given the surprisingly strong inflation data in recent weeks, they need to continue hiking rates until the data changes in order to retain their credibility, and to prevent markets expecting any material weakness to result in a pivot to easier policy, or a reinstatement of the central bank put. Indeed, we saw the European Central Bank raise rates by 50bps on 16 March, a clear signal that it is still focusing on its inflation-fighting credentials, at least in the short term.

On a longer-term perspective, these developments call the overall approach to bank regulation and governance into question. Despite extensive regulatory reforms, the banking sector is once again a potential source of crisis and contagion for the wider economy, and is turning to governments, central banks and, ultimately, taxpayers for support. Once the immediate urgency of the crisis has passed, hard questions are likely to be raised around the position of private banks in modern economies, and whether the state should play a stronger role.

Only time will tell whether this crisis proves to be a turning point in the battle against inflation, or whether further interest rate hikes are required. Cool heads are as important as ever in navigating this volatile and uncertain new regime, but a disciplined, long-term approach should continue to be pursued.

What this means for portfolio strategy

We don’t believe this is an environment where bravery in portfolio construction will be rewarded, and are maintaining a modest underweight to global equities in client portfolios, together with some additional portfolio insurance where permitted.

While the downward shift in sentiment and increasing likelihood of a recession are positive for bond valuations, we remain conscious that the long-term global trends of ageing demographics, deglobalisation and climate change are likely to mean elevated inflation over the coming decade, which will be a long-term headwind for bond yields.

Outside of the banking sector, the improvement in the inflation and interest rate outlook in the past week is generally positive for valuations, but we are cognisant that a lot of corporate leverage has built up during the low interest rate environment. A selective approach focusing on companies with strong balance sheets generating healthy cashflows and dividends is therefore appropriate.

Within alternatives, we have reduced exposure to areas more exposed to higher interest rates – such as private equity and long-dated infrastructure – but we remain positive on investments in less correlated areas, such as carbon credits, gold and absolute return funds, which benefit from structural tailwinds.

We are carefully monitoring the fallout from the failure of several banks in the US, but at this stage we do not expect this will lead to a global recession. While some parts of the economy are slowing sharply, such as the property sector, the baton is being passed to new growth drivers, such as China’s re-opening and the global capex boom needed to fund the climate transition. Despite increased volatility this week, global equity markets have still delivered positive returns in the year to date. We believe that, as this new investment backdrop continues to evolve, there will be material opportunities for disciplined and opportunistic investors.

1Bloomberg, US Federal Reserve, 16 March 2023

2US Bureau of Labor Statistics, February 2023

3Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, data as at end 2022. Insured call report filers only

4HSBC, Strategic acquisition to strengthen HSBC’s banking franchise in UK, 13 March 2023

5Bloomberg, Credit Suisse Seeks Circuit Breaker With $54 Billion Line, 16 March 2023

Important Information

If you are a private investor, you should not act or rely on this document but should contact your professional adviser. This communication is sent on a confidential basis, and you are welcome to discuss the materials with our staff. This information may not be circulated to others without our permission.

The information on which the document is based has been obtained from sources that we believe to be reliable, and in good faith, but we have not independently verified such information and no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy. All expressions of opinion are subject to change without notice.

US Persons are able to invest in units or shares of Sarasin & Partners LLP funds if they hold qualified investor status and enter into a fully discretionary investment management agreement with Sarasin Asset Management Limited. US persons are U.S. taxpayers, nationals, citizens or persons resident in the US or partnerships or corporations organized under the laws of the US or any state, territory or possession thereof.

This document has been prepared by Sarasin & Partners LLP (“S&P”), a limited liability partnership registered in England and Wales with registered number OC329859, authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and approved by Sarasin Asset Management Limited (“SAM”), a limited liability company registered in England and Wales with company registration number 01497670, which is authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority and registered as an investment adviser with the US. The information in this document has not been approved or verified by the United States Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) or by any state securities authority. Registration with the SEC does not imply a certain level of skill or training.

Please note that the prices of shares and the income from them can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested. This can be as a result of market movements and also of variations in the exchange rates between currencies. Past performance is not a guide to future returns and may not be repeated. Management fees and expenses are described in SAM’s Form ADV, which is available upon request or at the SEC’s public disclosure website, https://www.adviserinfo.sec.gov/Firm/115788.

For your protection, telephone calls may be recorded. SAM and/or any other member of Bank J. Safra Sarasin Ltd. accepts no liability or responsibility whatsoever for any consequential loss of any kind arising out of the use of this document or any part of its contents. The use of this document should not be regarded as a substitute for the exercise by the recipient of his or her own judgment. SAM and/or any person connected to it may act upon or make use of the material referred to herein and/or any of the information upon which it is based, prior to publication of this document.

© 2023 Sarasin & Partners LLP – all rights reserved. This document can only be distributed or reproduced with permission from Sarasin & Partners LLP.