How do we begin to understand the damage caused by the pandemic? The year 2020 saw the greatest contraction in the global economy since World War II, and a fall more than double the size of that caused by the global financial crisis in 2009 (Real GDP, USD terms, World Bank).

Governments stepped in, providing an unprecedented level of fiscal support, and are now confronted with record levels of debt. The arrival of effective, safe vaccines has provided a possible route back to normality, but like any other recession, the shock to the economy is likely to cause long-term scarring. Given the scope and duration of the crisis, the damage is significant, with a variety of short- and long-term effects. Yet, crises can not only inflict damage, but also inspire a kind of creative destruction with the opportunity to address long-standing structural problems and help lift potential economic growth.

Recovering to the pre-covid size economy

The COVID-19 recession has been a recession like no other. Economic recessions are typically the result of external shocks, like the oil price shocks of the 1970s, asset price bubbles, or aggressive increases in interest rates to ward off spiralling inflation. There is no rulebook on how to manage the impact of infectious diseases on the economy. China’s government, having had the experience of the SARS outbreak in 2002, set what then quickly became the global template for governments around the world – lockdown and limited physical mobility.

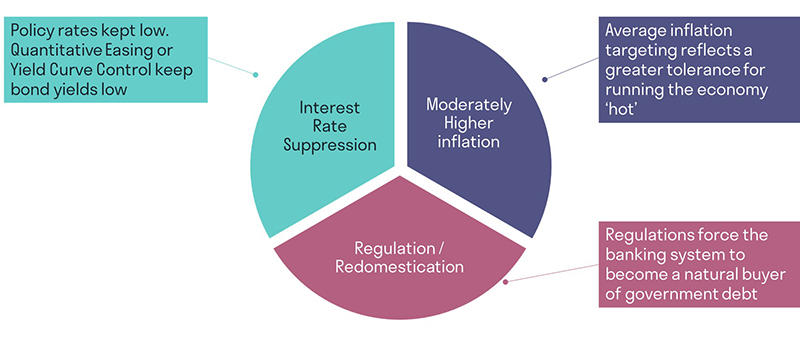

To counter these restrictions, which mostly affected the service sector, governments acted decisively and aggressively to support their economies. The IMF estimates that the fiscal response, coupled with the sharp decline in output and government revenue, pushed global public debt close to 100 percent of GDP in 2020 – the highest on record. The development of effective vaccines has provided a ray of hope and a possible path back to normality. Yet, given the depth of the damage, varied size of the services sector across countries, and the uneven distribution of vaccines, the global recovery will be uneven. On average, we estimate that countries will take two to three years to heal. China, which implemented a very strict form of lockdown but for a relatively short period of time, completed this process in just one quarter. The US, fuelled by fiscal stimulus, is likely to recover to its pre-COVID sized economy by mid-2021. These differences are likely to compound over time: we expect that China’s economy will be almost 25% larger by by the end of 2023. By contrast, the UK, which is also processing the additional shock of leaving the EU, is likely to be 1-2% larger.

Policy implications and financial repression

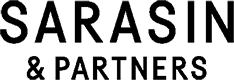

Looking further ahead, we expect that policy makers will address the post-COVID landscape by resorting to financial repression policies, yet again. Financial repression is the idea that central banks suppress interest rates in order to boost growth and to manage elevated debt burdens. Firstly, this requires interest rates to remain low, even as economies begin to recover. Second, inflation is likely to creep moderately higher as central banks increase their tolerance for inflation. In the US, the Fed has moved to a new policy framework of average inflation targeting, which means that periods of low inflation - like last year - will need to be made up with higher inflation in the future. Third, regulations – such as liquidity requirements and risk weightings in capital calculations for banks – will be tilted to ensure that the banking system remains a large natural buyer for government debt. Financial repression is essential because it enables policy makers to create an environment where nominal interest rates run lower than inflation, thereby creating an environment of negative real interest rates. Through financial repression, governments will be able to better manage high debt levels – because growth rates will be higher than the interest cost of debt. So, even as the economy recovers, we expect real interest rates to remain negative.

The risk of long-term unemployment

Recessions also tend to leave long-term scars, permanent effects that last long after the initial shock to the economy has faded. Perhaps most concerning is the potential impact on the labour market.

During the last recession, the unemployment rate rose from 4.5% to 10% in the US. As the economy improved, some of those who were unemployed were able to transition back to employment, some were discouraged by their search efforts and left the labour market altogether, and some remained stuck in long-term unemployment – generally defined as being unemployed for more than 12 months. It is this rise in long-term unemployment which makes the overall unemployment rate sticky, and why it takes on average seven years for the unemployment rate to return to its pre-crisis lows. The duration that a person is unemployed has long-term consequences.

Just before the pandemic hit, the long-term unemployed accounted for 12% of the total US unemployment pool. In the UK, it accounted for around a quarter of all those unemployed, in Japan it was just above 30%, and an astonishingly high 57% in Italy1. Structural factors largely explain these cross-country differences. The crisis, where it has affected certain sectors and countries more sharply, may have exacerbated these variations, as well as indeed the government policies implemented to address the crisis itself.

Even before COVID, the world was moving towards a data-driven virtual future. The pandemic has brought about a huge step change

In the US, where policy has been focused to protect household incomes with large stimulus cheques, the labour market has been allowed to respond to the changing conditions – with about half of the 20 million jobs lost already re-employed. In the UK and Europe, policymakers cognisant of the risk of entrenched unemployment instead chose to subsidise workers’ pay by introducing furlough and short-term work schemes. Yet, as the crisis has become extended, these policies have prevented some of the resource re-allocations needed. Research from the Brookings Institute estimates that 42% of the jobs lost in the pandemic could be gone permanently in the US. The authors argue that much of the changes in our behaviour – in how we have worked and consumed during the pandemic – will persist over time. And preventing the necessary reallocations will only weaken and prolong the economic recovery.

Could creative destruction help us solve deep-rooted problems?

By disrupting lives and livelihoods, the pandemic has placed the world at a critical juncture. In their book, Why Nations Fail, Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson define critical junctures as major events that disrupt the existing political and economic balance. Critical junctures can unleash a force of creative destruction, launching nations down very different paths. The Black Death is one such example.

Following the labour shortage caused by the plague’s death toll, Western Europe moved away from the feudal system and market forces took hold, setting the stage for the renaissance and eventually the Enlightenment. Eastern Europe, in contrast, facing the same labour shortage, resorted to greater repression, leading to the Second Serfdom, which persisted for two hundred years. So as Western Europe emerged from the Black Death with more inclusive institutions, Eastern Europe became more extractive.

Even before COVID, the world was moving towards a data-driven virtual future. The pandemic has brought about a huge step change. As businesses and households rewire to new ways of working and living, investment spending in information processing equipment, software and R&D has lurched upwards. This is in sharp contrast to investment spending on structures and ‘old economy’ equipment. As we emerge from COVID, we might finally – after more than a decade – witness a sharp pick up in investment that can raise productivity, wages and ultimately growth. Studies also suggest that in the future roughly 30% of jobs can be done remotely in advanced economies without losing any productivity2. This could help offset some of the demographic challenges facing rich economies – such as aging and declining population growth – improving the long-term outlook for global growth.

Decades from now, when we look back on COVID-19, we are likely to think of it as a critical juncture. It has been hugely disruptive, upending our way of living and working, but also with the potential to create lasting positive change.

1Source: OECD

2Source: McKinsey Global Institute, 2020